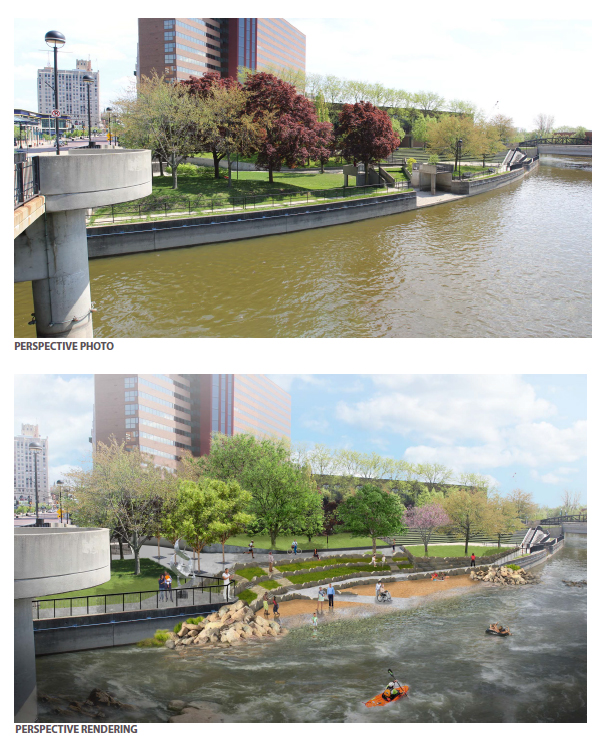

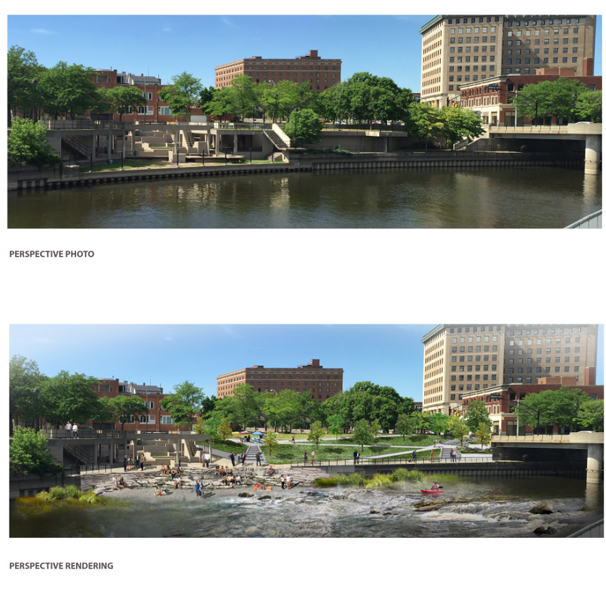

They see a safe and clean place for ample fishing of walleye and bass. And a place for paddling a kayak or canoe on a warm sunny day through downtown Flint. Organizers of the estimated $40 million Flint River Restoration project say returning the river to its natural state will accomplish much more than just making it safer and improving the water quality.

Returning an about six-mile stretch of the Flint River to its naturally flowing state also provides accessibility to the river — something that will bolster economic development and tourism in Flint and Genesee County, those working on the project say.

Earlier this year, the superstructure of the deteriorating Hamilton Dam, classified among the most dangerous dams in the state of Michigan, came down. The dam near the University of Michigan-Flint campus was built in 1920 to aid the logging industry and later helped the automotive manufacturing sector.

A smaller Fabri Dam built in 1979, located downstream from the Hamilton Dam, also was removed.

“While we’ll be working under construction for quite some time, you’re already seeing the excitement and momentum building just from the removal of the dam,” said Janet Van De Winkle, project manager for the Flint Riverfront Restoration at the Genesee County Parks and Recreation Commission.

The weir at Hamilton Dam remains and will be part of the river restoration’s next phase that aims to return the river to its natural flow and shape, Van De Winkle said. The shoreline also will be softened to create safe ways to enter the river, she said.

“Once those dams are opened up, you can go from Mott Lake all the way out the watershed to the Shiawassee Natural Refuge and you keep going, it’ll just take you out to Saginaw Bay,” Van De Winkle said.

A focus of the project includes waterway that curves through downtown Flint and two university campuses. A large concentration of the project is converting the General Motors Co.’s former Chevy in the Hole manufacturing site into Chevy Commons, a green, park-like space with walking and biking trails.

“The broad goal is to connect the two universities through the riverfront and the downtown, so that it’s a focal point for the area,” said Barry June, acting director for the Genesee County Parks. “That’s going to bring more people in through the downtown areas, give people access to the river so there’s more opportunities for fishing and for people to actually touch the river as opposed to looking at it.”

Planning for the Flint River Restoration began nearly a decade ago and involved stakeholders from the city of Flint, Genesee County, Genesee County Land Bank and other government agencies. Also involved are the Flint River Watershed Coalition, businesses, such as Wade Trim, local foundations and others. The project also was incorporated into Flint’s master plan.

More than two years ago, the Genesee County Parks division took over as lead organizers on the project in partnership with the city, Van De Winkle said. And a $3-million dam management grant from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources helped kick off a large chunk of the work.

“The Hamilton Dam was kind of the linchpin of the entire project and kind of the inspiration behind the entire project because with that dam in place, fish passage wasn’t happening upstream of the dam and we couldn’t have recreation downstream of the dam,” said Van De Winkle, who worked on the Flint River Restoration project with the Flint River Corridor Alliance before joining Genesee County Parks. “And it really inspired a whole vision around the whole Flint River corridor.”

Money from that DNR grant also is going to repair 71 city-owned stormwater outfalls along the river that go from downtown to Carpenter Road, which will aid water quality, Van De Winkle said.

River restoration, concentrated between Carpenter Road and Chevrolet Avenue, will continue for an estimated four to five construction seasons once construction permits approvals are secured from numerous state and federal agencies, June said. Work first will be focused on the downtown area, he said, with the possibility of being wrapped up by the end of summer 2019.

“The Flint riverfront is going to be really a game-changer for the downtown area when it’s creating … a beautiful, viable riverfront that will engage the public.”

Mark Young, chairman Genesee County Board of Commissioners

Mark Young, chairman of the Genesee County Board of Commissioners, said while job creation and investment may be marginal, he believes the restoration will provide a great deal of value in attracting businesses and retaining younger residents.

“The Flint riverfront is going to be really a game-changer for the downtown area when it’s creating … a beautiful, viable riverfront that will engage the public,” he said.

Young said kayaking opportunities, plus bike and walking trails will help sell downtown Flint to prospective businesses who want to provide employees with a great quality of life.

“We think this will actually be a very good recruiting tool as well as a good benefit to all the citizens of Genesee County,” he said.

Young said the rehab of the river and riverfront will help give young residents who want to be active a reason to stay in the area.

Genesee County Parks officials have not conducted an economic analysis of the Flint River project. But, Van De Winkle points to other reports for similar projects including a 2014 study on the Grand Rapids Whitewater Project along the Grand River.

The Grand Rapids project, though larger, includes removing dams, work on the riverside, creating river access points and enhancements such as parks. An economic impact report commissioned by the nonprofit Grand Rapids Whitewater and conducted by Anderson Economic Group LLC of East Lansing estimates the recreational use elements of the Grand River restoration would stimulate new economic impacts between $15.9 million and $19.1 million a year. It would also generate at least 80 new jobs, with new visitors spending money in restaurants, hotels, shops and other businesses. Property values and taxable values also could increase.

“It’s just time that we restored the river back to, as much as we can, its natural channel design….,” Van De Winkle said. “It’s going to provide another era of economic impact for the community. But this time it’s more based on quality of life and recreation for the people of Flint and Genesee County.”

So far, about $30 million of the needed $40 million has been raised through a variety of federal and state grants and private funding, Van De Winkle and June said.

The Hagerman Foundation in Flint provided $200,000 to the Flint River Corridor Alliance and Flint River Watershed Coalition to pay for preliminary engineering design work.

“We knew we were taking a risk to grant dollars to a project like this, but knew the outcome was worth the risk,” Phil Hagerman, president and founder of The Hagerman Foundation, said in a statement. “We looked at other river restoration projects nationally and saw the economic development that resulted when communities embraced their rivers and natural resources. Supporting these types of projects is vital to the future of Flint and its residents.”

The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation of Flint also provided $5 million in funding.

“Numerous cities across the U.S. have used river restoration as a catalyst for economic growth in downtown business districts — many with great success,” Ridgway White, president of the Mott Foundation, said in a statement. “We expect similar results here. A vibrant river with an attractive waterfront will draw more people to downtown Flint, which means more customers and more revenue for local restaurants, bars and other businesses.”

A large piece of the project involves the more than 60 acres at Chevy Commons along the Flint River near Kettering University. The site of the historic Sit-Down Strike in 1936-37 in recent years had become a concrete covered eyesore.

Kettering University also helped to acquire some of the needed land for the project.

“The university benefits tremendously from the energy the river restoration has created, and we are doing a number of complementary activities – from the $2-million Atwood Stadium restoration to the 21-acre Kettering University GM Mobility Research Center nearing completion on the Flint River,” Jack Stock, Kettering’s director of external relations, said in a statement.

Three of five phases of the Chevy Commons transformation are complete, with the fourth phase slated to wrap up in the fall, June said. The final phase is aimed for completion by the end of next summer, he said.

People already are using parts of Chevy Commons for bike riding and walking. It’s also become a lunchtime spot for Hurley Medical Center staff, Kettering University employees and students and others to enjoy.

When complete, Chevy Commons will include bridges across the Flint River for pedestrians to walk to Atwood Stadium or downtown, June said.

“As far as the neighborhoods, on the south side of Chevy Commons, their view is a heck of a lot better than it was,” June said.

The University of Michigan-Flint’s campus borders part of the river and the university provided access on its property for removal of Hamilton Dam, said Michael Hague, UM-Flint vice chancellor for business and finance.

“It looks so much better with that dam out of there,” he said. “Just the aesthetics of what that part of the project has already done, not to mention the safety…. From our point of view, that just looks really good.”

U-M Flint also gave Consumers Energy access to the river and property so the utility could remove contaminants from the site of a former manufactured gas plant. That work is separate from the Flint River restoration.

Hague is looking forward to seeing more concrete come down. He said he sees people fishing in some parts of the river now, and when the river is fully open, he expects the water access will bring more people downtown and to campus.

There’s also talk of UM-Flint offering kayaks for students to use, Hague said.

“That’s going to be really good for our students,” he said. “It’s just so many more things to do.”